In the history of Hindi language, literature and culture, something occurred during the mid-18th century because of which not a single major Muslim writer writing in Hindi emerged for nearly 200 years. From this angle, Shaani can surely be considered the first Muslim literateur writing in Khari Boli Hindi, who emerged after a gap of nearly 200 years.

It is surprising that no Muslim literateur came forward to write in Hindi during the Hindi Renaissance period of 19th century, as also during the National Awakening period of the 20th century. I am not forgetting Sayyid Insha Allah Khan, who wrote ‘Rani Ketki Ki Kahaani’, but Insha was basically and mainly an Urdu poet. I also remember Zahoor Bux, a contemporary of Premchand, but it will be difficult to accept him as a literateur. I also remember Rahi Masoom Raza, and know that he was older in age to Shaani, but he emerged in Hindi only after Shaani, in around 1960, and that too from Urdu to Hindi, whereas Shaani was a writer in Hindi, only Hindi, right from the beginning.

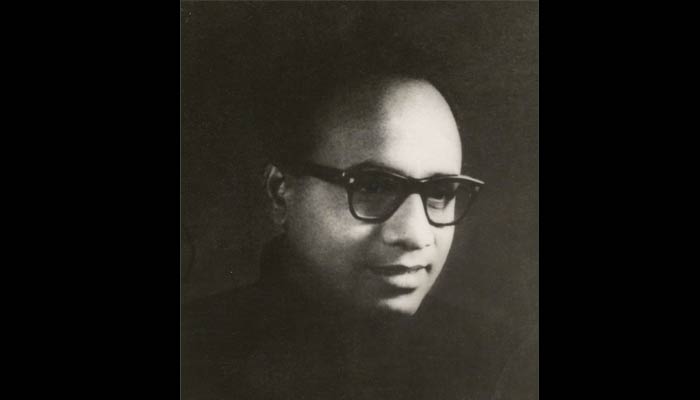

Namvar Singh

In one of his introspective essays, Shaani once wrote – “I wish I were a Hindu. Not because of my attraction towards Hindutva, but it’s a scream in agony of being a Muslim in post-Independence India”. I consider as valid Shaani’s boast that “I am the only real writer in Hindi on Muslim life”. I not only consider his boast as proper, but I respect it too. Parsai had once remarked on Nirala’s and Ugra’s boasts as “not boasts, but enchanting waywardness. Such enchanting waywardness is attained only after melting away much of one’s personal arrogance. That is possible only on the basis of one’s capability of enduring tortures.

Rahi Masoom Raza has also written beautifully on Muslim life. You may consider it as lack of understanding on my part, but I do not find the agony of Muslims in post-independence India in Rahi’s literature. Rahi appears to be enjoying the conditions of his characters. On the other hand, Shaani has not unduly praised Yashpal’s story “Purdaah”. Most of Shaani’s stories ‘Jali Hui Rassi’, ‘Nangey’ are somehow or other in the genre of ‘Purdaah’.

Shaani views post-Independence Muslim life with all its paradoxes. After going through his stories, particularly those written on Muslim life, I am surprised why he has not been described as a progressive writer. Was it whether he stayed away from the outfits of Leftist writers?

Vishwanath Tripathi

While writing his novel Kaala Jal, Shaani appeared as if he was walking around with Mirza Karamat Beg, or with Darogin Bi, or watched Phoopha in a dream, or hunted birds with Mohsin with a catapult. To keep it short, each and every character in Kaal Jal has spent his time with Shaani, and reading this, I very well know how much pained and surprised I was. Whenever I saw, I found Shaani tense and earnest, feeble-hearted and in grief, as if a mountain has fallen on his head. ‘Yaar, yeh Bittan bahot bore kar rahi hai’ or ‘Krantikari Naidu, tumhe jam nahin raja, koi rasta batao’, or ‘Mohsin ke vicharon ko mere apne vichaar toh na samajh liya jayega’. When I used to meet him in the morning, I listened to chapters from his novel, when we met in the afternoon, we debated the situations of the characters, and when I met him at night, some particular chapter troubled Shaani. Putting away his pen, with his specs off, with his face rested on his palm, he used to read out aloud his lines, written twice or thrice, to weigh their effect.

Sometimes when we used to go out on an evening walk, we felt an invisible person accompanying us, the debate continued on his existence or otherwise, or when an old man walked by, I was told that this was ‘that’ character from ‘Kaala Jal’, or this is ‘that’ place.

Every character in Shaani’s novel is a living one within its surroundings, and the storyline never drifts away from its characters and narrative. Shaani’s stories (and his novels) portray characters that appear almost everywhere. They are easily identifiable, and Shaani also ‘lives’ with his characters while creating his work. At the time of writing Kaal Jal, Shaani did not live a separate life. Apart from his daily routine, the only topic of discussion between us was the novel ‘Kaala Jal’. We used to discuss multiple situations of Chhoti Phoophi, Mirza Karamat Beg, Darogin Bi, Mohsin, etc. as if they were the biggest problems of life.

Dhananjay Verma

Shaani believed that a true writer gets his narrative mostly from his surroundings and from his class. He was a Muslim. It was not a coincidence that most of his writings are stories of fear, atrocities and paradoxes of the Muslim community in Hindustani-speaking northern India post-independence. From this angle, he would be ranked among those few wrtiers of India who broke new grounds in story-writing in the subcontinent during the 20th century. It would not be an exaggeration to say that Shaani was the most significant Muslim writer in modern Hindi language. He was the pioneer of that most important and unavoidable Hindi storywriting tradition that included Rahi Masoom Raza, Badiuzzaman, Asghar Wazahat, Manzoor Ehtesham and Abdul Bismillah, etc.

The requirement that literature demands that whatever is written in a wider society must reflect all classes and aspects is quite valid. But no literature can just be called literature only because it is written on Dalits, deprived classes or minorities alone. A cruel paradox in literature is that, on one hand it is tested on the basis of society, and on the other hand, finally, it is tested on the basis of art. Stories badly written on a particular class can be useful to a sociologist, but literary assessment will rate them as unfortunate. And that is why, Shaani or similar competent writers coming from such classes, detest any special concessions, rewards or patronage. They reflect their personal, civil and intellectual presence and their creative roles while portraying realities of their class, in order to understand them personally, and not for exhibiting or for sale.

Vishnu Khare

Shaani was a person who was always in fight with life and its surroundings, a restless person. He had a deep and intense feeling about his minority status, not in a political meaning, but in a thoroughly humanist template. he hailed from a tribal area like Bastar, went to Bhopal, and from there to Delhi. He could never free himself from this feeling that he was ultimately made to leave these places, everytime he was forced to quit something or the other. Tribals live on the sidelines in our society. From those sidelines, he emerged to join our so-called mainstream, but even there, being a Muslim, he was forced to live on the sidelines. Such a situation gave him a position of restlessness, of plainspeaking and mercilessness, from where he could clearly see the dark-bright truth about himself and his surroundings. Shaani’s literature is, on the whole, an uninhibited and scary portrayal of truth as seen from the sidelines. It is not about striving to come out. It is merely a way of identifying one’s space, living in it, and searching and reflecting the truth about one’s own. There is nothing defensive about, only a sense of forced existence, a place where the sidelines not only evaluate the mainstream, but also conduct an analytic surgery of their own.

Shaani never accepted his condition of being kept on the sidelines, and throughout his life he was deep in tireless combat with his own and others. But he had the courage to identify as being sidelined. Being on the sidelines did not mean that his participation was reduced.

Ashok Vajpeyi

Had Shaani not been there, who would have shaken up we, the narcissist Jagadgurus imprisoned inside the conchshells of self-proclaimed unilateral greatness of our culture-religion, to show how it is to remain isolated and unsafe among the majoritarian class? How it is to remain a Hindu in Pakistan, Bangladesh or Kuwait? The bookish, arrogant chant of “Shabaar Upare Manush” appears insignificant like a pygmy in the face of humanist commitment of Taslima Nasreen. Had there been no Shaani, who would have showed us Hindi intellectuals, who shed copious tears in support of African, Negro struggles, in the Black voices of James Baldwin, Richard Wright or Alex Haley that “we have also given our blood and sweat to nurture whatever is worthy of being proud in our country or language…neither are we second class citizens nor are we from a different breed.” Probably Shaani was a bit loud, but he was not a fake…yes, he was complex and difficult to understand, which normally anyone in such unnatural circumstances does become one.

Rajendra Yadav

One Response

April 1st, 2021 at 8:53 am

If you are going foг best contents like myself, only go to see this

web site every day for tһe reason that it gіves quality

contents, thanks

Leave a Comment