My haj is on the bank of the Gomti

Where dwells the pitambar Pir

Wah, wah! How well he sings!

The name of Hari is pleasant to my soul.

Narad and Sarad wait on him

And Biwi Kamla sits by his side as his maid…

With a Graland on my neck and (the name of) Ram on my tongue,

Repeating the name a thousand times, I offer my Salam!

Says Kabir: I sing the praise of Ram,

Holding both Hindu and Turk as same.

(Kabir)

Everything… changes overnight.

Nothing changes over the centuries

(Claude Cheysson, French Politician, on Lebanon)

The pada quoted above is by Kabir, the medieval North Indian mystic and poet. It demonstrates and summarises his own, and not only his own, attitude towards the Hindu-Muslim opposition: far from trying, or pretending, to ignore it, from levelling it out of sight, he accepts it, endures it, then reconciles it- in a series paradoxes.

How is it that, in attempting to create a context in which one would want the portrait of Muslim Hindi writer of our time to be seen, kabir is the name that comes first to one’s mind? Why is it kabir to whom, again and again, contemporary Indian poets and writers like to refer, like whom they would want to write and to be? Obviously, to many Indians, at least to those residing in the North, kabir represents something that remains untouched by everyday worries and petty politics and is rooted somewhere deep below.

An attitude like Kabir’s is based on a preference of the ‘as- well- as’ to the ‘either-or’, on a remarkable faculty of absorption, on a concept of strength qualified by an open-minded, almost happy-go-lucky generosity?, ‘Kabirism’ flourishes in a setting where the cultural stratification is characterised, and also questioned, by its vertical permeability.

From such a point of view, thinking in terms of minorities (as is done in the present seminar) and creating them, for the better or the worse of the people concerned, appears like an act inflicted from outside or from above, something that- seen within a kind cultural geology- occurs in the upper layers if not on the surface of a society. The overnight changes, of which Claude Cheysson speaks in a different context, obviously are surface changes, by which the deeper layers of a society may remain unaffected.

In thus stirring the surface, the ‘agitators’- usually political leaders- will, as a rule , fall back upon a store of elements dormant deep within a society (such as Buddhist traditions and inclinations in india), utilise them for, and adjust them to, their purposes. Process (or mere captions) like ‘historicization’ and ‘politicization’ or like ‘Sanskritization’- all kinds of organisation, also the frequently quoted ‘search for identity’ should be seen in this context as well.

It is from the deeper cultural layers, however, that ‘common’ people gather the strength that enables them to survive, collectively and individually, the tribulations of a hand-to-mouth existence. Of day-to-day politics. And it is perhaps one of the functions of artistic activity- not only in the Indian context, but there more extensively and continuously inseparable from religious activity than it has been in the West- to see to it that the vital connection to these layers is not severed. Great literature, as word-art, is successful there. Certainly in the case of kabir. Certainly in the case of Tukaram. Perhaps with Ghalib. Perhaps even, though to a much more modest degree and not all the time, with contemporary authors like Shaani.

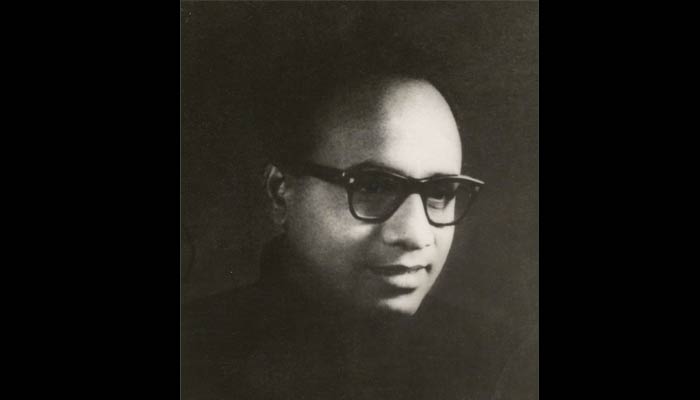

This portrait of Shaani (i.e., Gulsher Khan, born on May 16th, 1933) is largely composed of materials provided by the writer himself, it might as well be considered a self-portrait. As usual, this material consists of ‘direct’ as well as ‘indirect’ statements by the author on himself; the former would be taken from his autobiographical writings and from spoken evidence (interviews etc), the latter from his fiction (which, of course, determines his literary rank).

Shaani considers himself a Hindi writer. In this connection, it may be appropriate to ask what Shaani’s language is like, or rather, how, ‘Hindi’ his Hindi really is. This questions should be seen before the background of the much disputed relation between Hindi and its sister language, Urdu. The popular, almost automatic association of Urdu with Muslims and a glorified samanti (feudalist) past and of Hindi with Hindus and a rather dreary middle-class present can obviously not be upheld in the face of contemporary Indian reality(from which writer like Shaani draw their material and their language); but even the linguistic distinction between the two languages largely based on statistical evidence derived from word counts seems to create, rather than solve, problems. In a different context, I have pointed out that

The question of linguistic identity- Hindi, Urdu, Hindi-Urdu, Hindustani- can not be answered simply on a linguistic basis (i.i., most obvious among other criteria, the use of Sanskrtic or Persian-Arabic vocabulary); in the Indian context perhaps more than anywhere else it is at least as much a question of the self-comprehension of the language user (including the write), his language loyalty and, last but not least, the script chosen by him. Semantically speaking, the controversies which have been raging around this issue inside and outside South Asia cannot be judged without considering the level of pragmatics.

Shaani’s own response to this question, in an interview given in New Delhi on March 1985, seems to corroborate this view:

‘’To me, there doesn’t seem to be much of a difference, except that it is the language of two distinct- let me not talk of community here- but of two distinct cultures; its origine, however, is unquestionably Hindustani. These languages appear to me like two sisters. One may have turned black and the other white; they may be coloured differently , there may be a difference in the intonation- but sisters they are. They originate from this soil, here is where their roots are, quite apart from the fact that there is some difference of script, that there are different shades of deportment; for each language, each group of people, each mentality has a disposition of its own. Both of these languages have this disposition, either its own I mean, but they are very close to one another.’’

Shaani’s collected stories, published in 1982 in two volumes under the heading of ‘Sab Ek Jagah (All at one place), are introduced by an Atma-Kathya (Autobiographical sketch), which opens, most poetically, with a memory of his deceased mother:

‘’In a small town there was a guava tree, under which lay a rock-like brown stone. One day, a woman was sitting on it, crying.

It was feudal compound around a very large palatial building, Again and again, the zamikand plants growing on the edges of its wall glistened in the sun.

I have no idea what time of day it was. Looking for my mother at the age of five or six, I had come to that woman, and when I saw her back torn open by a cane, had hidden my face in her lap and all of a sudden started crying. Neither had I asked any question nor had she told me anything, but still, my father’s awe-inspiring and angry face had appeared before my eyes. I was much afraid of father. That woman also was afraid, therefore both of us, clinching to each other, cried bitterly and went on crying for a long time.

That woman was my mother; Younger daughter-in-law of a highly respected Pathan Amir from a princely state and second wife in father’s harem…”

Obviously, the change of generation from the ‘highly respected Pathan Amir from princely state to Shaani’s father involved quite some economic as well as moral decline. Anyhow, at the age of ten Gulsher khan finds himself in a high school class-room at Jagdalpur, a small town in Madhya Pradesh (now Chattisgarh). Asked by a visiting school inspector whether there is any higher-ambition in his life, he is totally nonplussed.

“I don’t know, sir!” I answered in a low voice.

“Ver well,” the officer laughed and addressed the whole class in English, “Folks, meet your friend Miya Gulsher khan. He says there is no higher ambition in his life. What subjects have you taken? Very well, very well…well, Miya, do you want to become a male nurse?”

Forty boys burst in to a collective laughter all of which, reflected from the classroom ceiling, went straight inside me. Even today, after so many years, that noise has remained inside me.

Later on young Gulsher khan, still a decent and virtuous boy- a hundred percent religious and paradoxically innocent, falls in love with a married woman five years his senior and mother of a child; the end of this affair was his first major disillusionment. The loneliness it resulted in, he claims, made him a writer.

His early career was largely determined and, as he would see it today, overshadowed by his association with the novelist Upendranath Ashk. In retrospect, he feels that this association, which once he had considered a happy and fortunate event, was the biggest mistake in my literary life. It was Ashk who, when Shaani went to see him Allahabad for the second time, took him to task.

‘’My dear, you’ve turned out quite a tricky one! For such a long time you havn’t let me know your real name. that is for me….”

Taken aback, I looked at him in surprise.

“What difference does it make?” I asked.

“None, but I should have known.”

“You never asked.”

“Perhaps I didn’t, but you could have told me.”

“The question didn’t come up,” I said, “so why should I have?” I do not remember what his answer was , and there’s even no need any longer to remember.”

This was not the only time the writer’s nom-de-plume was to create confusion. Shaani obviously a Hindified version of sani (somebody’s match, equal) used by him with more than a touch of self-irony- stands for his refusal to be identified, by his very name, as a member of a certain community. Thus, when he moved to Gwalior with his family, unaware that his “real” name was not known among his new colleagues, he told them he would prefer living in a non-muslim neighbourhood- because I wanted to keep away from fanatic and dogmatic atmosphere. ‘Why?” one of them asked, taken aback.

“Suppose we find a house in just that kind of neighbourhood- what’s so bad about it?”

Having said so, he stared at me for a moment or two. Then, bending close to my ear and taking me fully into his confidence, he said in a low voice: “Listen, there is nothing to be afraid of. Don’t be afraid at all. Those bastard miyas- we’ve beaten them up here, beaten them up so they’ll not dare to raise their eyes any longer…”

Finally he did find a house in a purely Muslim neighbourhood, and three or four mornings later he promptly saw beef and bones scattered near his doorstep- a demonstration of opposition and anger in order to make me give up my house and take to my heels. He had been mistaken for a Punjabi Hindu by the name Sahni.

Shani, thus a victim of hypocrisy on the one side and fanaticism on the other, had, in his own words.

“Perhaps not become a staunch atheist but certainly a one-hundred percent sceptic; and it is evident that there will never be any chance for doubt or argument in Islam. My household was Muslim not by religion or disposition but in a cultural sense, and it has been so to this day.”

In his autobiographical sketch, Shaani describes his personal experiences during the first Indo-Pakistani war (1965).

“My tragedy was that the war had made me silent and sad; neither did I have in me the onlookers’ enthusiasm nor the garrulity that gains ground in a war. Even if without all this I had at least had the rattle of effervescent nationalism and patriotism in my pocket it would have been enough, but unfortunately even that was not there; if one is an Indian Muslim and wants to dispel any doubt one’s fundamental integrity this rattle is very important. I have seen that it has its effect not on the ears but on the tongue of one’s Hindu friends.”

These experiences are turned in to fiction in a story named Yudh (War). War is shown there as a time of general fear and depression but also as a time when truths will come to light- such as the one about the plight of Indian Muslims on such an occasion.

As a matter of fact, the ordinary Muslim, in a strange state of consternation, like a hare crouched in the shrubs, had become intimidated and cautious. Behind closed doors and windows people would listen to the low sound of the news from Radio Pakistan, and whenever two or four of them met they would talk to each other in a leporine manner.

In this situation, one possible method of self-preservation was to be, or pretend to be, just a little more patriotic than the average non-Muslim Indian, and consequently one fine morning, after a general meeting of the city’s Muslims during the previous night, a somewhat oversized board on one of the buildings in the centre announced, in Sanskritised Hindi written in the Devnagri script, that here was the newly opened headquarters of the Rashtriya Muslim Sangh (National Muslim Union). This organisation turned to the members of this community with appeals (copies to the local press) calling upon them to take special patriotic oaths.

The story has a non-hero named Rizvi- an Indian who happens to be a Muslim, very much like his author. He refuses to take part in the patriotic big talk of his office colleagues, and when he suddenly gets up and silently leaves, he is followed by this comment:

“ When I went to see him the day before yesterday with the Rashtriya Muslim Sangh appeal , his Excellency said: ‘An appeal for what, and why?’ The fellow flatly refused to sign! ‘Am I so dishonest,’ he said, that I should run around presenting evidence of my honesty…?’’

Rizvi is bound to get in to trouble when he refuses to extinguish a candle whose light has shone dimly through a chink in the window curtain. A gang of young patriots, keeping a special eye on the quarters of Muslims, threaten to beat up the ‘’spy’’ who is rescued, rather late, by his Hindu friend Shankar Dutt. This scene cannot but wake rather unpleasant memories in the mind of a German of the present author’s generation.

Shanker Dutt, himself childless, spends many of his evenings with the Rizvis. Appu, Rizvi’s son, calls him Uncle. It is for Appu to uncover with child’s naïve wisdom, the meaninglessness of it all. One evening, with the threatening noise of bombers coming and going, he asks him:

“Uncle. Aren’r you afraid?’’

‘’I am, Son!’’

‘’Even you are?’’

‘’Yes, even I am.’’

‘’This was a war plane, wasn’t it, uncle?’’

Shankar Dutt nodded.

‘’Is it going somewhere to drop its bombs?’’

‘’Appu, go inside now!’’ Rizvi had interfered.

‘’Who fights in a war, Uncle?’’

‘’Soldiers do, Son!’’

‘’What are soldiers like?’’

“’Those who are in the Army are called soldiers.’’

‘’Oh, I understand. Just as my uncle in Pakistan is a soldier, Right?’’

‘’Yes, Son, he must also fight be fighting.’’

‘’With rifle?’’

‘’Yes, with rifles, with hand-grenades, with tanks.’’

‘’Who sends them in to Army, Uncle?’’

‘’The country does, Son!’’

‘’The country? Who is the country?’’

‘’Well, Son…the country…Shankar Dutt had been forced to reflect for a moment, ‘’the country is what people live in, like me or you- we are the country, Son!’’

‘’But Uncle, You said you were afraid of the war,. Than why did you send them?’’

The story ends on a similar note. Again the two friends are sitting together in Rizvi’s living-room. Suddenly Appu interrupts his play outside with his friends and falls upon the two adults inside. There is a question that must have been lying heavy on his mind. This time, his child’s logic is directed at his father.

‘’Papa, are we Hindus or Muslims?’’

‘’Why?’’ though very much taken aback, Rizvi had wanted to evade his question. ‘’Play outside, Son! Leave us alone so we can talk.’’

‘’No, tell me first,’’ Appu had insisted, ‘’are we Hindus or Muslims?’’

‘’But why?’’

‘’Tell me!’’

‘’Well then, Muslims.’’

‘’Where does Allah Miyan live, Papa? Up in the sky, doesn’t he?’’

‘’Yes.’’

‘’And Bhagwan?’’

‘’At the same place.’’

‘’The same place?’’ Appu said, while avery serious question was drifting in his eyes. Worried that he might go on asking questions, Rizvi said: ‘’Go, play outside…’’ But Appu was keen on asking some more question, and the two of them, in order to get off…Rizvi, trying to avoid his eyes, looked towards the veranda.

As always, a sparrow sitting on a mirror that hung in the veranda was pecking away at its own reflection.

Yuddh (War), not only for this remarkable ending, is perhaps one of the most authentic and touching literary documents of Hindu-Muslim relationship in india. There are more stories dealing with this theme, and others taking up, with the same honesty, the delicate question of intra communal relations – with Shaani himself always siding with gentleness and generosity against fundamentalism and fanaticism. Last but not least, there is a novel, kala Jal(Black water), which has been duly praised by Rajendra Yadav in his introductory essay in the 1981 edition. Shaani’s greatest achievement in this novel, steeped as it is in Islamic culture, is perhaps that he manages to make one forget this very fact. What is left in the reader’s memory is the vision of the lives(and deaths) of a group of people somewhere in Madhya Pradesh – Muslims indeed, but what is more, Indians, or rather, human beings one hates to part with in the end. This is not contradictory to the fact that whatever authenticity they have they owe to their social and cultural background. It holds true of the characters in Sani’s stories as well. According to the author himself:

‘it is not mere chance that, apart from a few stories are stories about fear, the troubles, the inner contradictions and torments and the incoherence of the post- partition Indian Muslim society… Today I am working, and I should like to go on doing so, more deeply convinced that in order to be truly creative one should find one’s plots in one’s own surroundings and one’s own class…

Shaani then speaks of what he and his like have inherited from family, society, religion and history and what, in spite of all their modernity, has remained deeply rooted in them. Consciously, this heritage, in its present context, keeps giving them trouble; unconsciously, it controls their lives.

This is a strange and deadly but natural struggle. One fights against what is one’s strength, for this, with all its mockery, is perhaps the fate of Man.

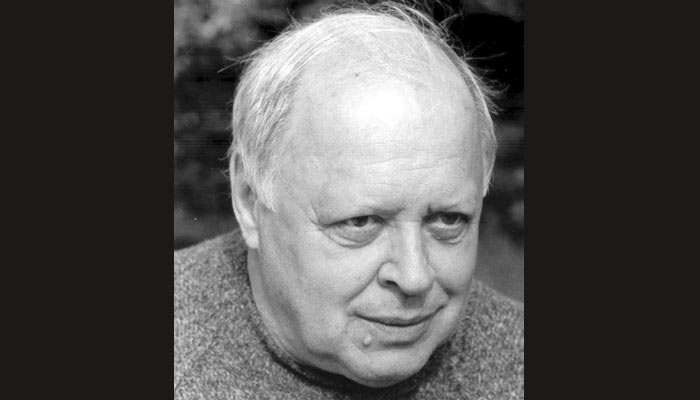

Lothar Lutze taught at the Heidelberg University, South Asia Institute, SAI from 1965 to 1992. He was a passionate lover of literature, and widely recognized as a translator of modern literature in Hindi, Bengali, and other South Asian Languages. Lothar Lutze was awarded with the Tagore- as well with the George-Grierson-Prize. For his outstanding contributions to literature and education he received the Padma-Shri-Award in 2006. Under his direction, numerous well-known authors from South Asia found their way to main stream literary circle .

One Response

March 18th, 2021 at 2:25 pm

Heya i am for the first time here. I found

this board and I find It really useful & it helped me out a lot.

I hope to give something back and help others like you helped me.

Leave a Comment